Triangulation

Triangulation

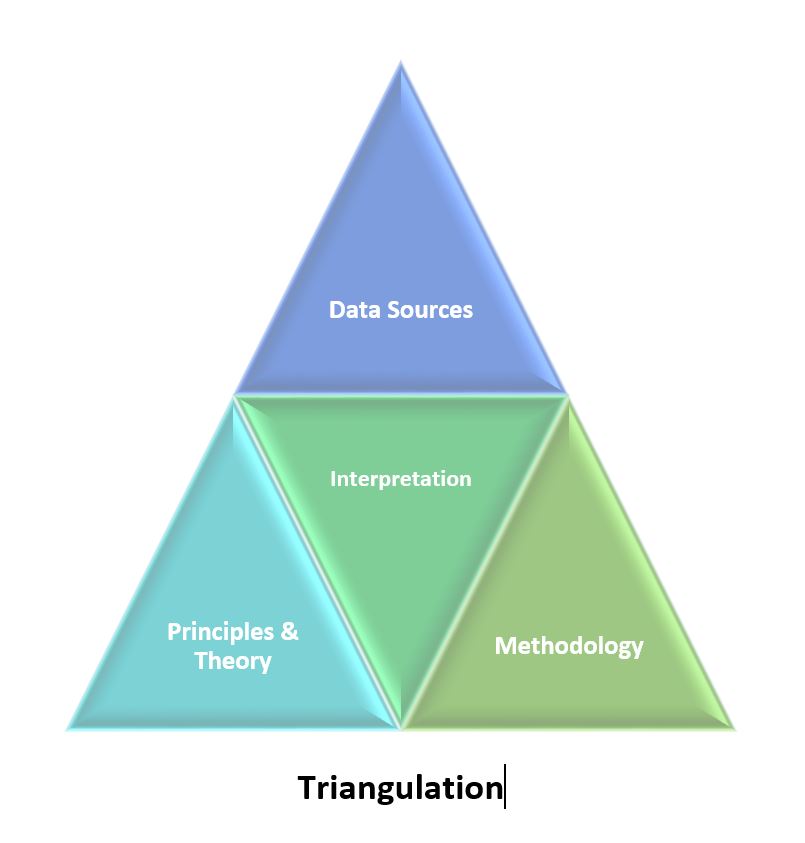

- Is a critical concept in research, education and life. It "refers to the use of more

than one approach to the investigation of a research question in order to enhance

confidence in the ensuing findings," (Bryman, n.d., p.1)

- Utilization of multiple data sources and materials, multiple data perpsepctives, methods and/or approaches

- Including varied data analysis including: qualitative; quantitative; expert review; logic and patterns; precedent; established principles and theory

- Triangulation increases validity and reliability.

Miles & Huberman (1984, p 234) use the following example to explain triangulation:

Detectives, car mechanics, and general practitioners all engage successfully in establishing and corroborating findings with little elaborate instrumentation. They often use a modus operandi approach, which consists largely of triangulating independent indices. When the detective amasses fingerprints, hair samples, alibis, eyewitness accounts and the like, a case is being made that presumably fits one suspect far better than others. Diagnosis of engine failure or chest pain follows a similar pattern. All the signs presumably point to the same conclusion. Note the importance of having different kinds of measurement, which provide repeated verification.

Five Forms of Triangulation

(Denzin, 1970; Denzin & Lincoln, 1998)

- Data triangulation - entails gathering data through several sampling strategies, so that slices of data at different times and social situations, as well as on a variety of people, are gathered

- Investigator triangulation - refers to the use of more than one researcher in the field to gather and interpret data

- Theoretical triangulation - refers to the use of more than one theoretical position in interpreting data

- Methodological triangulation - refers to the use of more than one method for gathering data

- Environmental triangulation - referes to the use of different locations, settings and other key factors related to the environment in which the study occurred

More on Triangulation

- The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research

- The Use of Triangulation Methods in Qualitative Educational Research

- What is Triangulation (Qualitative research)? (B2B Whiteboard Video)

References

- Bryman, A. (n.d.). Triangulation.

- Denzin, N. (1970). The research act in sociology. Chicago: Aldine.

- Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. 1998. The landscape of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing

- Miles, M. & Huberman, A. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Validity & Reliability

Compiled by Colin Phelan & Julie Wren, Graduate Assistants, University of Northern

Iowa, Office of Academic Assessment (2005-06)

Reliability

- Is the degree to which an assessment tool produces stable and consistent results.

Types of Reliability

- Test-retest reliability is a measure of reliability obtained by administering the same test twice over a

period of time to a group of individuals. The scores from Time 1 and Time 2 can then

be correlated in order to evaluate the test for stability over time.

- Example: A test designed to assess student learning in psychology could be given to a group of students twice, with the second administration perhaps coming a week after the first. The obtained correlation coefficient would indicate the stability of the scores.

- Parallel forms reliability is a measure of reliability obtained by administering different versions of an assessment

tool (both versions must contain items that probe the same construct, skill, knowledge

base, etc.) to the same group of individuals. The scores from the two versions can

then be correlated in order to evaluate the consistency of results across alternate

versions.

- Example: If you wanted to evaluate the reliability of a critical thinking assessment, you might create a large set of items that all pertain to critical thinking and then randomly split the questions up into two sets, which would represent the parallel forms.

- Inter-rater reliability is a measure of reliability used to assess the degree to which different judges or raters agree in their assessment decisions. Inter-rater reliability is useful because human observers will not necessarily interpret answers the same way; raters may disagree as to how well certain responses or material demonstrate knowledge of the construct or skill being assessed.

-

- Example: Inter-rater reliability might be employed when different judges are evaluating the degree to which art portfolios meet certain standards. Inter-rater reliability is especially useful when judgments can be considered relatively subjective. Thus, the use of this type of reliability would probably be more likely when evaluating artwork as opposed to math problems.

- Internal consistency reliability is a measure of reliability used to evaluate the degree to which different test items that probe the same construct produce similar results.

-

- Average inter-item correlation is a subtype of internal consistency reliability. It is obtained by taking all of the items on a test that probe the same construct (e.g., reading comprehension), determining the correlation coefficient for each pair of items, and finally taking the average of all of these correlation coefficients. This final step yields the average inter-item correlation.

- Split-half reliability is another subtype of internal consistency reliability. The process of obtaining split-half reliability is begun by “splitting in half” all items of a test that are intended to probe the same area of knowledge (e.g., World War II) in order to form two “sets” of items. The entire test is administered to a group of individuals, the total score for each “set” is computed, and finally the split-half reliability is obtained by determining the correlation between the two total “set” scores.

Validity

- Refers to how well a test measures what it is purported to measure. While reliability is necessary, it alone is not sufficient. For a test to be reliable, it also needs to be valid. For example, if your scale is off by 5 lbs, it reads your weight every day with an excess of 5lbs. The scale is reliable because it consistently reports the same weight every day, but it is not valid because it adds 5 lbs to your true weight. It is not a valid measure of your weight.

Types of Validity

- Face validity ascertains that the measure appears to be assessing the intended construct under

study. The stakeholders can easily assess face validity. Although this is not a very

“scientific” type of validity, it may be an essential component in enlisting motivation

of stakeholders. If the stakeholders do not believe the measure is an accurate assessment

of the ability, they may become disengaged with the task.

- Example: If a measure of art appreciation is created all of the items should be related to the different components and types of art. If the questions are regarding historical time periods, with no reference to any artistic movement, stakeholders may not be motivated to give their best effort or invest in this measure because they do not believe it is a true assessment of art appreciation.

- Construct validity is used to ensure that the measure is actually measure what it is intended to measure

(i.e. the construct), and not other variables. Using a panel of “experts” familiar

with the construct is a way in which this type of validity can be assessed. The experts

can examine the items and decide what that specific item is intended to measure.

Students can be involved in this process to obtain their feedback.

- Example: A women’s studies program may design a cumulative assessment of learning throughout the major. The questions are written with complicated wording and phrasing. This can cause the test inadvertently becoming a test of reading comprehension, rather than a test of women’s studies. It is important that the measure is actually assessing the intended construct, rather than an extraneous factor.

- Criterion-Related validity is used to predict future or current performance - it correlates test results with

another criterion of interest.

- Example: If a physics program designed a measure to assess cumulative student learning throughout the major. The new measure could be correlated with a standardized measure of ability in this discipline, such as an ETS field test or the GRE subject test. The higher the correlation between the established measure and new measure, the more faith stakeholders can have in the new assessment tool.

- Formative validity when applied to outcomes assessment it is used to assess how well a measure is able to provide information to help improve the program under study.

-

- Example: When designing a rubric for history one could assess student’s knowledge across the discipline. If the measure can provide information that students are lacking knowledge in a certain area, for instance the Civil Rights Movement, then that assessment tool is providing meaningful information that can be used to improve the course or program requirements.

- Sampling validity (similar to content validity) ensures that the measure covers the broad range of

areas within the concept under study. Not everything can be covered, so items need

to be sampled from all of the domains. This may need to be completed using a panel

of “experts” to ensure that the content area is adequately sampled. Additionally,

a panel can help limit “expert” bias (i.e. a test reflecting what an individual personally

feels are the most important or relevant areas)

- Example: When designing an assessment of learning in the theater department, it would not be sufficient to only cover issues related to acting. Other areas of theater such as lighting, sound, functions of stage managers should all be included. The assessment should reflect the content area in its entirety.

Ways to Improve Validity

- Make sure your goals and objectives are clearly defined and operationalized. Expectations of students should be written down

- Match your assessment measure to your goals and objectives. Additionally, have the test reviewed by faculty at other schools to obtain feedback from an outside party who is less invested in the instrument

- Get students involved; have the students look over the assessment for troublesome wording, or other difficulties

- If possible, compare your measure with other measures, or data that may be available.

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. (revised 2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: Authors.

- Cozby, P.C. (2001). Measurement concepts. Methods in behavioral research. (7th ed.). California: Mayfield Publishing Company.

- Cronbach, L. (1971). Test validation. In R. Thorndike (Ed.). Educational measurement (2nd ed.). Washington, D. C.: American Council on Education.

- Moskal, B. & Leydens, J. (2000). Scoring rubric development: Validity and reliability. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 7(10), 1-6

- The Center for Excellence in Teaching. How to improve test reliability and validity: Implications for grading. University of Northern Iowa